Robert Fossett knows all about how leadership skills learned in the military can set a veteran up for success in a career after discharge. Retiring as a Union Millwright after 30 years of service, Mr. Fossett used his military training to help him lead team members successfully on union jobsites.

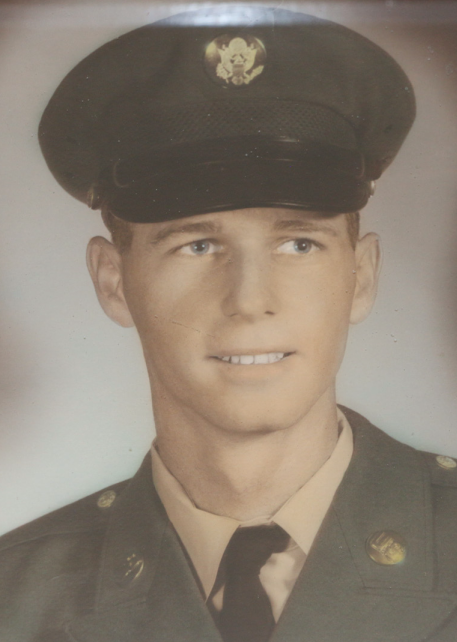

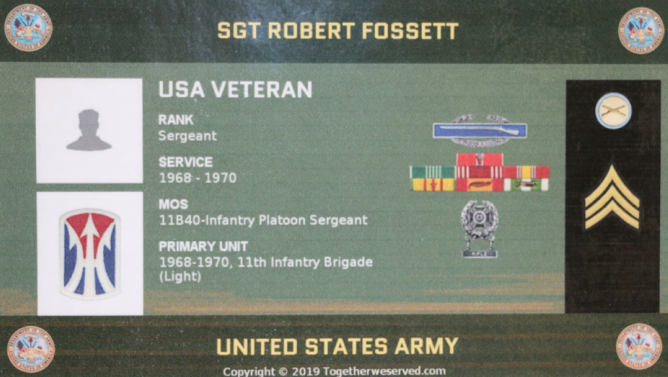

Drafted into the Army on October 23, 1968, Mr. Fossett completed his basic training at Fort Bragg in North Carolina where he got his first exposure to military leadership in the form of a big drill sergeant at the train station. Standing on the platform, the drill sergeant held a baseball bat in one hand and smacked it against the palm of his other hand as he told everyone to get off the train and hustle onto a bus. The Army broke recruits down and then molded them into the soldiers they wanted them to become. Fossett says the reason for the ruthless attitude of the drill sergeants at basic training was that “you gotta learn discipline and obey orders…especially in combat.”

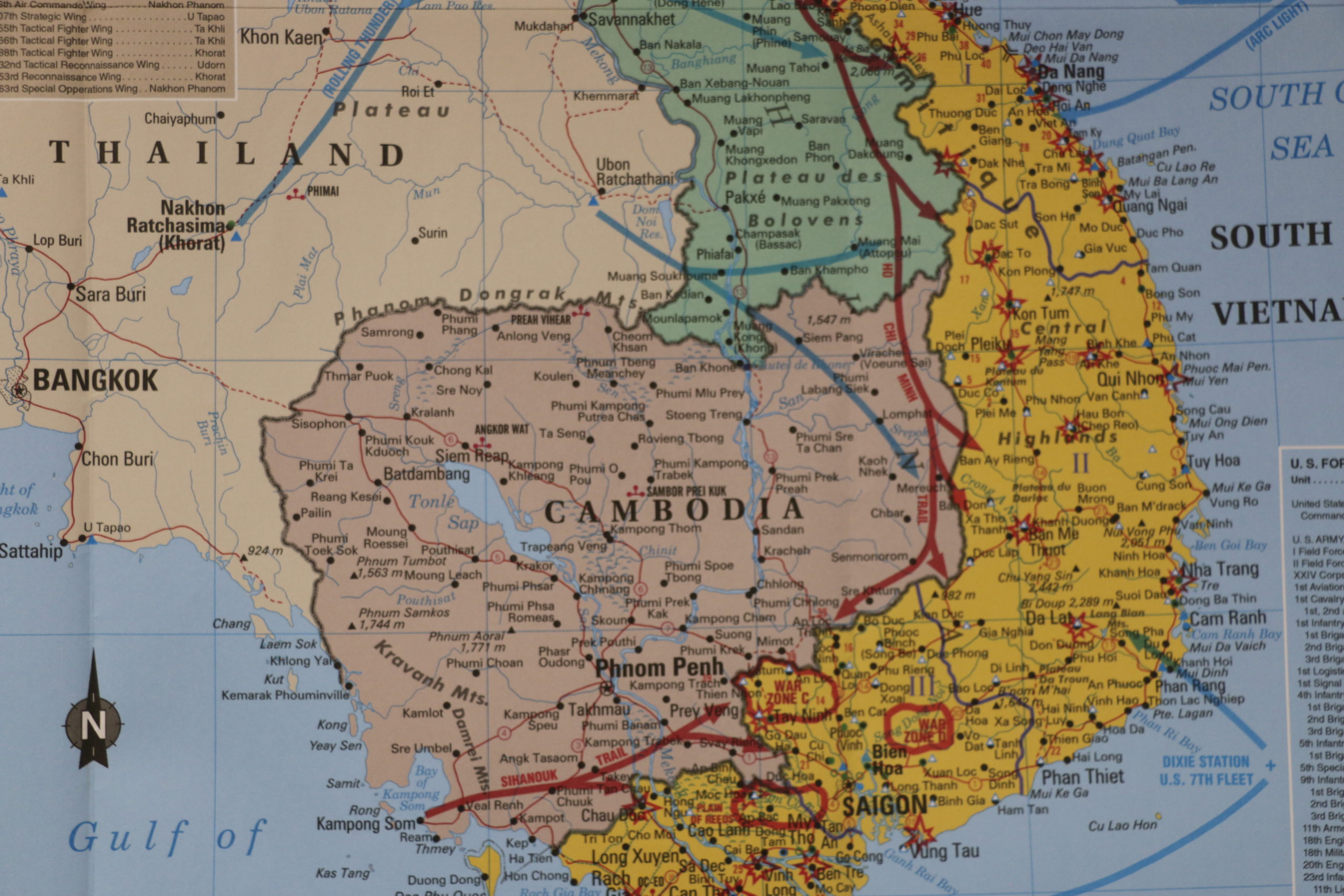

He then completed Jungle Warfare Training at Fort Polk, Louisiana. From there, the Army selected Mr. Fossett to attend the NCO (Non-Commissioned Officer) Academy at Fort Benning, Georgia where he graduated as a Sergeant E-5. During his time at Fort Benning, Robert learned one of his most critical skills, positioning and how to read maps. Knowing exact coordinates was the only way to get help as quickly as possible once in the jungle.

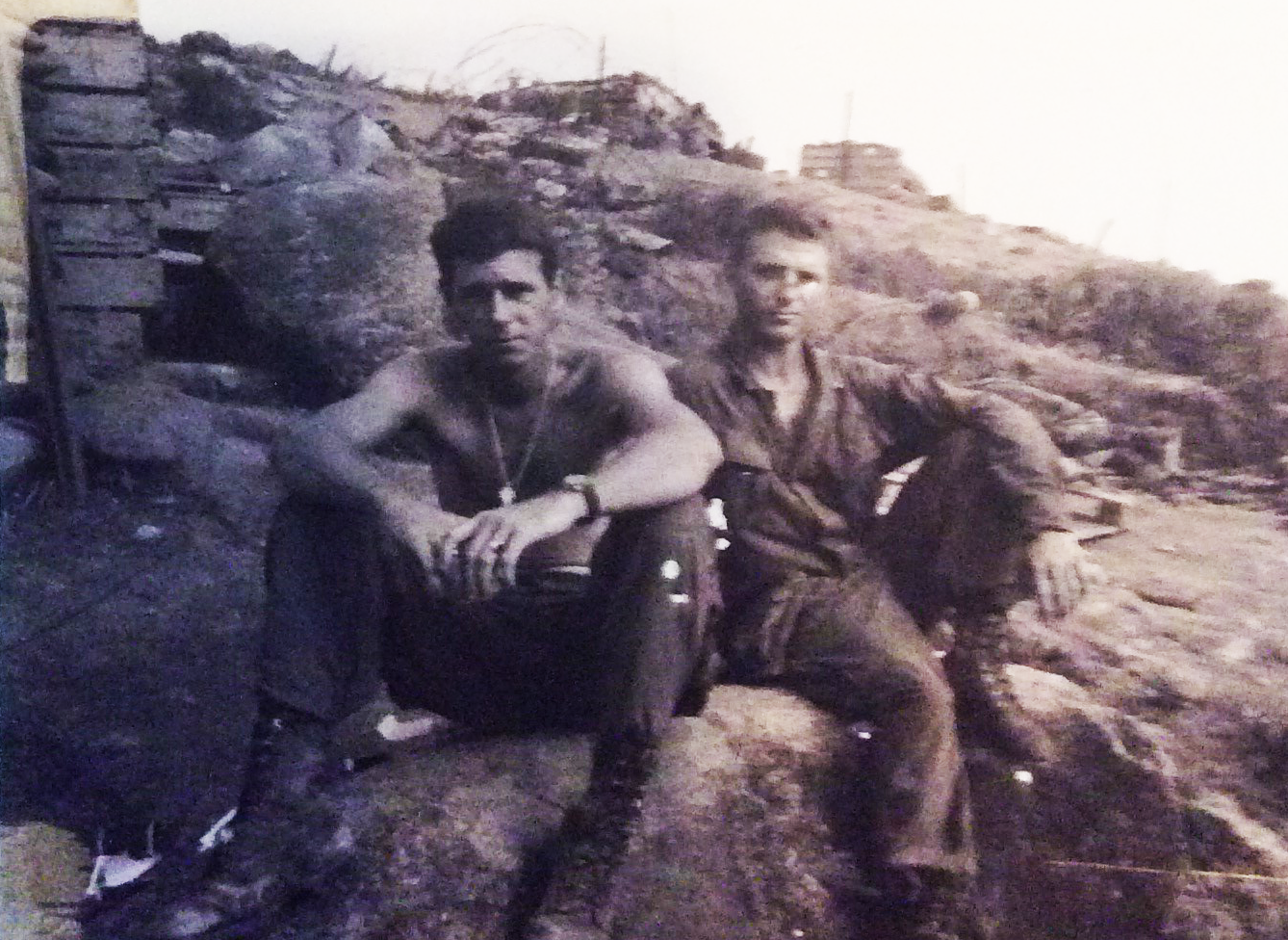

Mr. Fossett deployed to Vietnam on November 5, 1969. The Army assigned him to Alpha Company 4th Battalion, 3rd Infantry, 11th Infantry Brigade of the Americal Division. He was assigned a unit and trained with the sergeant he was to replace. For two weeks, the sergeant gave him tips on what to look for to do his job well. Book learning wasn’t all he would need to keep him and his men alive. Experience and hands-on training were essential to help ensure that he commanded his platoon right. That training would prove to be invaluable.

The conditions were, as he described it “extremely hot, and you’re in the middle of the jungle, in the middle of nowhere.” The Vietnam War was considered “air mobile”, meaning they would take soldiers by helicopter from one spot in the jungle to the other. A soldier in Vietnam could see up to 240 days of combat in one year, compared to a soldier in the South Pacific during World War II that saw around 40 days of combat in four years.

From enduring monsoon season to heading out on missions at night where he couldn’t see much in front of him, Mr. Fossett stayed focused on one goal, keeping his men safe. He was a young man with a year and a half or so of college under his belt. However, he was carrying a heavy responsibility in protecting the lives of over a dozen fellow soldiers.

Robert’s platoon would spend three weeks on search-and-destroy missions and then a week back at firebase, only to repeat it all over again. He described the experience as “everyday it’s the same thing, you don’t know if you’re going to wake up the next morning.”

Being a leader isn’t always easy.

As a Platoon Sergeant, Mr. Fossett was in charge of picking a guy to “walk point,” or be at the front of the platoon to identify ambushes, and he would pick a different guy each day. During one of their search-and-destroy missions they were going out on a five-day operation in the Central Highlands with two other companies when they were ambushed. Fossett’s point man was killed during the ensuing firefight and he has always looked back and wondered if things would have been different if he had chosen someone else that day. Would that soldier have lived?

From then on, he decided to walk point himself but with a soldier with an M-60 machine gun right behind him. This move helped him to identify the next ambush awaiting his men. He led by example and made the sacrifice to do one of the most challenging jobs himself. Fossett says that “I’m a firm believer that under extreme conditions, ordinary people can do extraordinary things.”

“I’m a firm believer that under extreme conditions, ordinary people can do extraordinary things.”

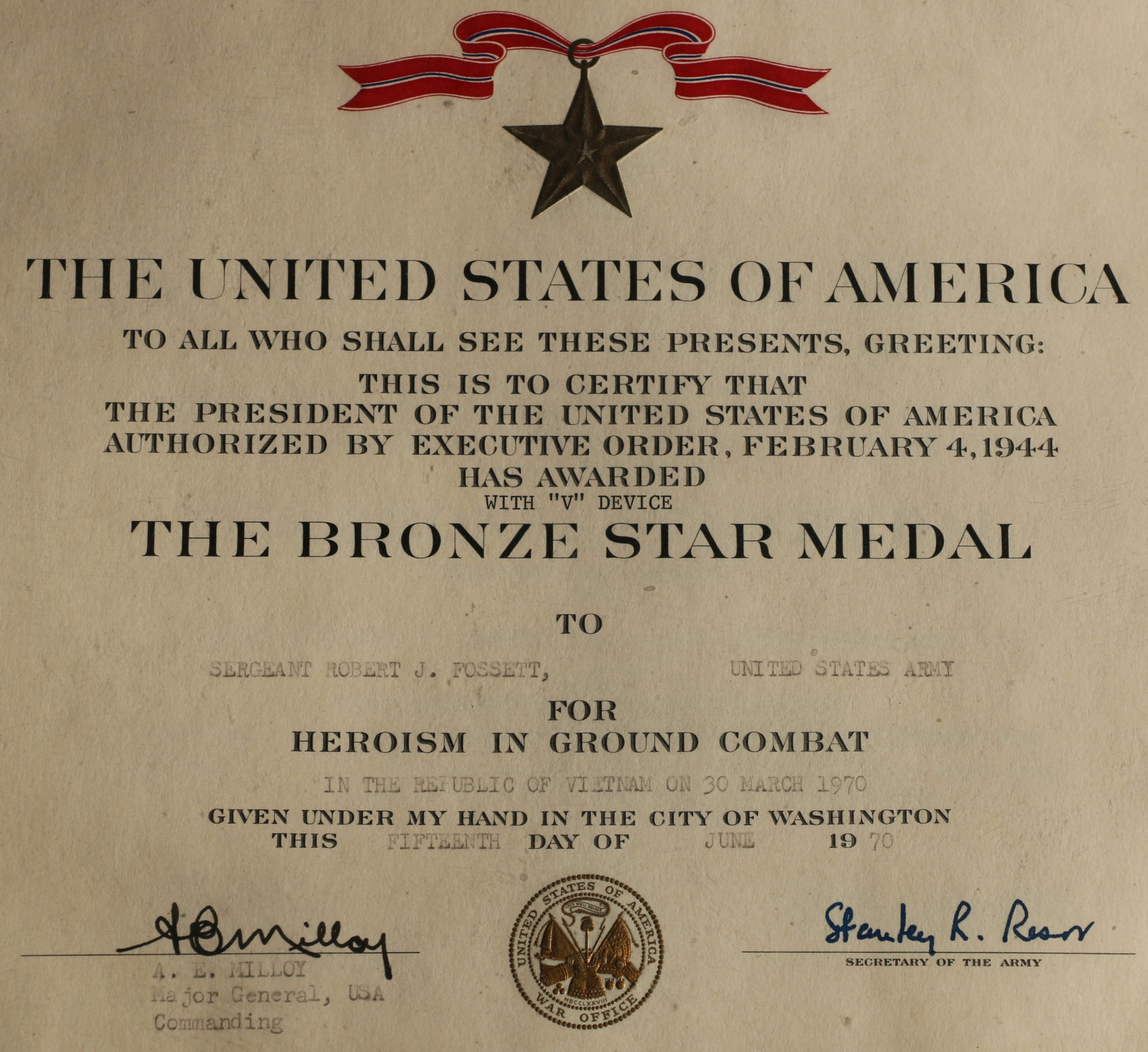

Fossett received his discharge in August 1970 and married in July 1971 to his wife Linda. They have two children, Mandy and Brad, and three grandchildren. During his time in the service, Fossett was in two major campaigns and earned two Bronze Star medals, one for valor and another for meritorious service. He also received the Army Commendation Medal and the South Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry as well as Vietnam Service Medal.

After working at Bell Telephone for three years, Mr. Fossett applied for and got accepted to the four-year apprenticeship program as a Union Millwright.

His time in Vietnam taught him the skills necessary to do his job well. He learned how vital being able to work well with diverse groups of people is. He worked with people from various walks of life and backgrounds, and it helped him to appreciate different perspectives.

He says that his military service “taught [him] to take charge. . .[to] not be afraid of taking charge. It helped in running jobs and being able to deal with groups of people.” . He learned how to “get. . .work out of” his employees but also to “work with them.”

One of the top skills he gained from his time as a soldier was to stay calm. Fossett says he doesn’t “rattle easy” and is “very calm most of the time about things” because he “had to keep a clear head. . .to make decisions.” His advice to his kids is “as bad as it seems, [to] take a deep breath, step back, and look at it, and say, ‘Okay, what are we going to do to fix this problem?’”

One of his most significant tasks was updating Millwright apprenticeship training manuals, at the Las Vegas Training Center, that hadn’t been updated in many years. As the job trade evolved, so did the tools. They got better and more technical. When he first started out, there were no lasers, but by the time he retired lasers had become prominent in the industry, shooting elevations, levels, and to do coupling alignments. What Fossett tells workers is to keep looking toward the future and to keep training.

Fossett would tell his fellow Union Brothers, fellow Retirees and all people, “to succeed in life remain calm in trying circumstances and to value the contributions of all colleagues. Additionally, it’s important to identify and act on any chance for training and advancement to stay current in fast-developing times”.